NFTs (explained later) are much in fashion at the moment. In the context of domain names, they have even been cited in a conflict with ICANN over the sale of certain TLDs (Top Level Domains). These NFTs are sometimes presented as good friends of domain names and at other times as rivals. Let us explore this complex relationship.

Non-fungible token?

An NFT (non-fungible token) is basically a pointer to a digital resource. It is not a physical object, nor is it a resource with a value per se (such as a work of art in digital form). The issuer creates an NFT (which can be sold to a third party) and makes it point to a digital (or sometimes physical) resource. The issuer declares in the blockchain that this person is the “owner” of the digital resource that this NFT points to. It can be likened to a certificate of ownership. If you hold a certificate stating “So and so is the owner of such and such a star” or “So and so is the owner of such and such a colour”, then people who trust the issuer of the NFT and the NFT system in general will acknowledge you as the owner.

Technically, the NFT generally takes the form of an automatic contract on a blockchain. First, a quick reminder of what a blockchain is. A blockchain is a technical mechanism for obtaining a consensus on a state among entities that do not know one another and that in any case do not trust one another. A state is, for example, a set of accounts denominated in a currency specific to this chain, with the balance of each account. This is what Bitcoin, undoubtedly the most famous blockchain, does. The accounts are generally identified by an address consisting of figures. (And we will see presently how to use names instead.) The important point about these chains is the absence of a central authority: anyone can take part and verify. So anyone can write information in the chain and no-one will be able to remove it arbitrarily.

The addresses are associated with a cryptographic key in two parts: the private part serving to authenticate the transactions on this address. Secure management of this private part of the key is therefore crucial. Do not store this key on an unprotected computer, for example. In practice, many users of blockchains do not manage the keys themselves but go through an intermediary who manages the keys for them. The security of this intermediary and the extent to which it can be trusted therefore become the crucial point.

Several blockchains offer a complementary mechanism: automatic contracts1. These are computer programs that handle data present on the chain. A user can thus make an automatic contract that manages the NFT and allows its transfer from one owner to another in exchange for a payment in the currency2 used by this chain. (The possible transactions often conform to the specification known as ERC-721. In broad terms, it allows transfers of an NFT from one account to another and recovery of the current owner’s address.)

The concept of NFT is much in fashion. Earlier systems, which shared certain characteristics of NFTs, in particular the fact that they were pointers as opposed to direct values, have now been renamed NFTs to take advantage of this fashion.

To what extent are these NFTs recognised, for example by the legal system? Are they really property? At present, the laws and regulations have not yet been constructed. As analysed by Noémie Bergez, a lawyer with the Dune law firm, everything is currently up in the air. As regards intellectual property rights, the author of the work retains ownership of the moral and patrimonial attributes of his or her work unless an assignment of copyright is provided by contract.

Note that, if the buyer loses the private cryptographic key giving him access to his account on the chain (or has it stolen), there is no recourse.

Another important point to note is that the value that might be attributed to an NFT depends entirely on the degree of trust accorded to its issuer. (Anyone at all can issue an NFT for anything at all, even without the author’s authorisation, and the same work may be pointed to by several NFTs. A NFT proves nothing, as regards authenticity.)

With this in mind, is an NFT “real property”? There is no obvious conclusion for now, since like any property, or like other concepts in our world such as money, recognition of the NFT depends on a social consensus3; if everyone recognises it as a certificate of ownership, then the NFT is a real certificate of ownership.

Domain names and blockchains

The idea of pointers is nothing new. An Internet address such as https://réussir-en.fr/app/uploads/2022/01/Infog-Barometre-2021-v5-800.png is a pointer to a resource (in this case a picture). The same applies to domain names, which are also pointers to useful information such as IP addresses for connecting to Internet servers. It was therefore logical to put these pointers in the blockchain and this old idea was implemented for the first time more than ten years ago, in the Namecoin blockchain. This idea had no success4, but it has reappeared from time to time.

We have seen above that the entities stored in the blockchain, for example user accounts, are identified by an address, such as for example (Ethereum chain) 0xbe1f2ac71a9703275a4d3ea01a340f378c931740. These addresses are not very practical to handle, and in certain cases we may wish to change them. For example, an automatic contract is at a certain address but we would like to roll out a new version of it to correct a bug. For these two cases, it would be good to have a naming system. Which is what ENS (Ethereum Name Service) provides. ENS is managed by a Singapore organisation called True Names, and the names have a syntax resembling that of domain names, with a suffix .eth5.

But be warned, they are not domain names, and are not recognised by a normal DNS resolver. If you wish to use one of these names, you will have to be prepared to carry out a few computing tasks. In any case, their main use is to name resources on the blockchain. In theory, they can also be used to point outside this chain, for example to the IPFS decentralised hosting system. We might therefore imagine websites pointed to by an .eth name and hosted on IPFS6, but in practice this is very rare.

From this point of view, .eth names are very close to being alternative roots, which aroused a degree of interest many years ago. Like them, their attractiveness depends on the number of users and the social consensus that we mentioned above. Intrinsically, a .eth name has the same “value” as a .fr name. What makes the difference is the number of users that recognise this name and can use it. One of the reasons for the failure of alternative roots was that users were required to pay to have a name which served no purpose, in the absence of users or belief in their imminent arrival7.

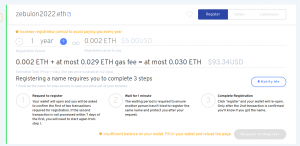

If you wish to explore .eth names, there is at least one public explorer8, https://app.ens.domains/9. Thus https://app.ens.domains/name/wikipedia.eth/details allows you to obtain information on wikipedia.eth10. Registering one of these names has a direct cost with the company that manages ENS and an indirect cost, the “gas” crypto-fuel that is what is paid to the machines (the miners) that make the chain work. At present, the bulk of the cost of ENS names consists of the cost of gas, with a typical name costing between €40 and €50.

Figure 1: How much will it cost me to register zebulon.eth in ENS?

We have said that ENS names ended in .eth, but in fact it is not as simple as that. An existing domain name can also be linked to ENS in order to use a classic name. Note that this possibility is announced for certain top level domains only11, but that it is not a technical obligation. Verification of the legitimacy of this link depends solely on DNSSEC12 and could work with any TLD.

Use of NFTs

What use are NFTs? The best known use is the field of contemporary art, to buy and sell works of art. For example in September 2021, a famous French rapper, Booba, sold the first title of his new album (“TN”) in the form of an NFT. He is the owner of the registered work. He created 25,000 NFTs enabling acquirers to view the clip, which is available exclusively via these NFTs, with the singer’s commitment not to release this content on other platforms. The NFT therefore allows the acquirer to access exclusive content. No technical details seem to be available, so it is difficult to know whether these are really NFTs and, if so, on what chain they are stored.

Figure 2: Booba calls on his fans to take their (crypto)wallets out

Of course, NFTs are not confined to rap; lovers of classical music may also be tempted, as may bibliophiles.

Another familiar use of NFTs is as a “property” title in a virtual world13. For example, we see private individuals and businesses buying “land” in these worlds. In the absence of public rules on this subject, the question as to whether this is real ownership remains open.

Another important point is that, although the blockchain allows direct verification by all (the content of the chain is public), in practice, the overwhelming majority of buyers of NFTs do not directly access the chain. They go through the Web server (or application) of an intermediary, and are therefore reliant on this intermediary and on the infrastructure used (for example, the domain name of the intermediary)14.

Are NFT and domain names linked?

In December 2021, a controversy involving NFTs and gTLDs15 arose following a refusal by ICANN to transfer 23 gTLDs belonging to the UNR registry (domiciled in the Cayman Islands tax haven).

The controversy arose when the UNR organised the sale by auction of a gTLD in the form of an NFT on the Ethereum blockchain. We should specify that each gTLD was sold in the form of a dedicated NFT. The principle of this sale was therefore that the acquirer of the NFT of a gTLD became the registry of the gTLD in question. One of the gTLDs, .hiphop, was sold in a more “classical” manner. What is more, they refused the NFT and even destroyed it, as can be seen with a public Ethereum explorer.

ICANN took a dim view of this sale. It decided to delay the transfer of ownership of the gTLDs sold in the form of NFTs, without specifying by how long. Why? Because ICANN is worried about the consequences of these transactions for the interoperability of the DNS and its capacity to act as authority for TLDs.

As regards the interoperability of the DNS, the technical question does not arise. The gTLDs sold as NFTs are and will remain gTLDs based on the DNS protocol and therefore subject to the authority of ICANN. Even if new naming practices appear in the blockchain systems to simplify things for users of crypto-currencies (a service offered by ENS), this will not call the interoperability of the DNS into question.

As regards ICANN’s ability to act on the TLDs sold as NFTs, nothing changes. The means of sale and the currency used have nothing to do with the technical functioning of the gTLDs on the DNS. Let us remember that blockchain is a peer-to-peer technology with no central authority, whereas gTLDs based on the DNS protocol are regulated by ICANN. ENS and DNS inhabit separate worlds, with different rules. It is therefore difficult to understand the reasons adduced by ICANN for delaying the transfer of these TLDs.

The subject is certainly more political, and we do not perhaps have all the elements to allow us to fully assess this conflict.

Conclusion

NFTs and domain names have one thing in common: they point to content. But apart from that they are very different. The domain name, intelligible by a user, points to a non-exclusive digital content intended precisely to be seen by as many Internet users as possible. The NFT, on the other hand, points to a resource that is generally unique, and allows the owner of the digital value of the content to be identified.

They do not work using the same technology: the domain name naming system is linked to the DNS technology, whereas NFTs are linked to blockchain technology.

Domain names have been in existence for more than 40 years and are used by the worldwide community of Internet users, whereas NFTs are still largely unfamiliar to the public at large and adopted rather by technology ‘geeks’ or investors.

We will no doubt see new NFT projects and practices in the coming months. It is exciting to observe the various different ways in which this new digital universe is evolving. However, we must be vigilant in assessing the value of these new projects.

In the specific case of ENS, the domain name is used as a tool to simplify access to users’ resources (for example their portfolio of crypto-currencies). The .eth name is therefore a means of democratising access to this new technology.

From our point of view, blockchain and NFTs should not be seen as enemies of the DNS protocol and domain names. On the contrary, we believe these technologies can serve one another and that we must keep watch on developments and adapt our practices to the evolution of these techniques.

1 – The are sometimes referred to as “smart contracts”, but the term is misleading. Like all computer programs, there is nothing smart about them. On the contrary, we want them to be “stupid”, blindly executing what we tell them to. This also makes it easier to verify them.

2 – For example, a crypto-currency of ethers in the case of the Ethereum chain.

3 – Criticisms of NFTs prefer to speak of shared illusion, but it is the same thing.

4 – Many names registered out of curiosity or in the hope of resale, but very little use.

5 – Note that ENS existed before the NFT vogue and that these names were not called NFTs before. This is just rebranding.

6 – One of the authors of this article has to confess that he has tried and unfortunately failed technically.

7 – Another reason was the wish to maintain unique names, the meaning of which did not depend on the user.

8 – What we would call in the world of domain names an RDDS (Registry Data Directory Service), such as the WHOIS protocol, for example.

9 – It is also possible to use a generalist blockchain explorer if there are the necessary ENS suffixes. Such is the case, for example, of Etherscan.

10 – Apparently unused (no content) and probably not linked to the free encyclopaedia.

11 – See, for example, the announcement made for .luxe.

12 – There are detailed instructions for this.

13 – The fashionable term being “metaverse”.

14 – Two pieces of advice if you are considering buying NFTs: make sure you have the address of the NFT on the blockchain, and look with an independent explorer, then check that you have the address of the corresponding automatic contract and that it can be analysed.

15 – Generic Top Level Domain. As a reminder, .fr is a ccTLD (Country-Code Top Level Domain) and as such not subject to ICANN rules.