Organised by ANSSI, the REMPAR25 cybersecurity exercise was conducted on 18 September 2025 with the participation of hundreds of French organisations, including Afnic. What is involved in this type of exercise?

The context

Hardly a day goes by without hearing of a cybersecurity attack: hospitals paralysed by ransomware, another personal database leaked or the website of an important public service down because of a denial-of-service attack. Protection against these attacks has become a major challenge for organisations. As so often in matters of security, regular drills with security methods and procedures are key. The aim is to test whether these methods and procedures work, whether employees know how to execute them and, as far as possible, to prepare for the day when they come under real attack.

But security is more than just a matter of drills, it’s a much richer and more complex area than this, one that goes beyond the scope of a single article. I’ll focus instead on describing the REMPAR25 exercise from the point of view of one of the participating organisations.

The scenario

The scenario chosen by ANSSI was that of a third-party breach of a widely-used software application within French organisations1. Attackers had supposedly managed to alter the software application in question, using what is known as a supply chain attack, so that on the appointed day, it would perform various malicious actions, such as shutting down other programs or extracting data.

This scenario has many similarities with the 19 July 2024 global outage of the CrowdStrike Falcon Sensor software. This widely distributed software2 had extensive permissions3, meaning that a CrowdStrike bug would cause all the systems running the software to crash. The result paralysed industries the world over, including air travel. The outage came from an error rather than a deliberate attack, but the consequences were nonetheless serious.

CrowdStrike’s Falcon Sensor is an EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) solution, a surveillance software that operates on all an organisation’s machines and keeps a permanent watch on all system activity (which is why it receives so many permissions, and also why bugs have such far-reaching effects). In the REMPAR drill scenario, a very common EDR had been altered by attackers and propagated among a large number of organisations on account of its automatic updates.

Around one thousand organisations took part in REMPAR25 – organisations of all sizes and sectors: prefectures, ministries, hospitals, local authorities, transport services, telecoms operators, Internet actors like Afnic, etc.

Conduct of the drill

A safety drill, whether it relates to cybersecurity or to the risk of fire, is never completely realistic. After all, we cannot set fire to premises to make the evacuation drill more closely resemble real conditions. So the “players”, the people involved in the drill, have to “play the game” and “do as if”. This has limitations, but that’s inevitable. In a real evacuation, heat and smoke from a real fire would complicate things, whereas in an evacuation drill one has to use one’s imagination.

With REMPAR, there was no question of launching real malware into the ecosystem or bringing services to a halt. In a real outage, one of the difficulties is not being able to rely on certain services that have become indispensable. In a drill, these missing services have to be simulated. In Angeline Vagabulle’s highly realistic novel “Cyberattaque” [Cyberattack], employees who no longer have access to the company telephone directory and no longer know telephone numbers by heart, have great difficulty contacting one another. They resort to personal connections “to call Dieter in Dubai, ask Cindy in Brussels, and to contact Cindy, I think Mehdi in Amsterdam knows her, and to call Mehdi, you can ask Valérie for his number – she’s in the building right now”.

So in practice, “stimuli” had to be used in the drill. These took the form of short texts sent throughout the day to the “players”. Depending on the organisations, these stimuli were sent by email or via the messaging system used by the organisation. They had been written by ANSSI but could be altered and/or supplemented by the local organisers. These stimuli were very varied, from an employee who asked to go home as he was unable to work, to an overzealous and misguided employee who wanted to go to the supermarket to buy a brand new computer, a disgruntled customer, a Chairman of the Board who wanted results immediately, and an opportunistic attacker who, taking advantage of the crisis, pretended he was with a cybersecurity company and requested access to the data centre. The players had to react to the stimuli, ignoring or dealing with them, as the case may be.

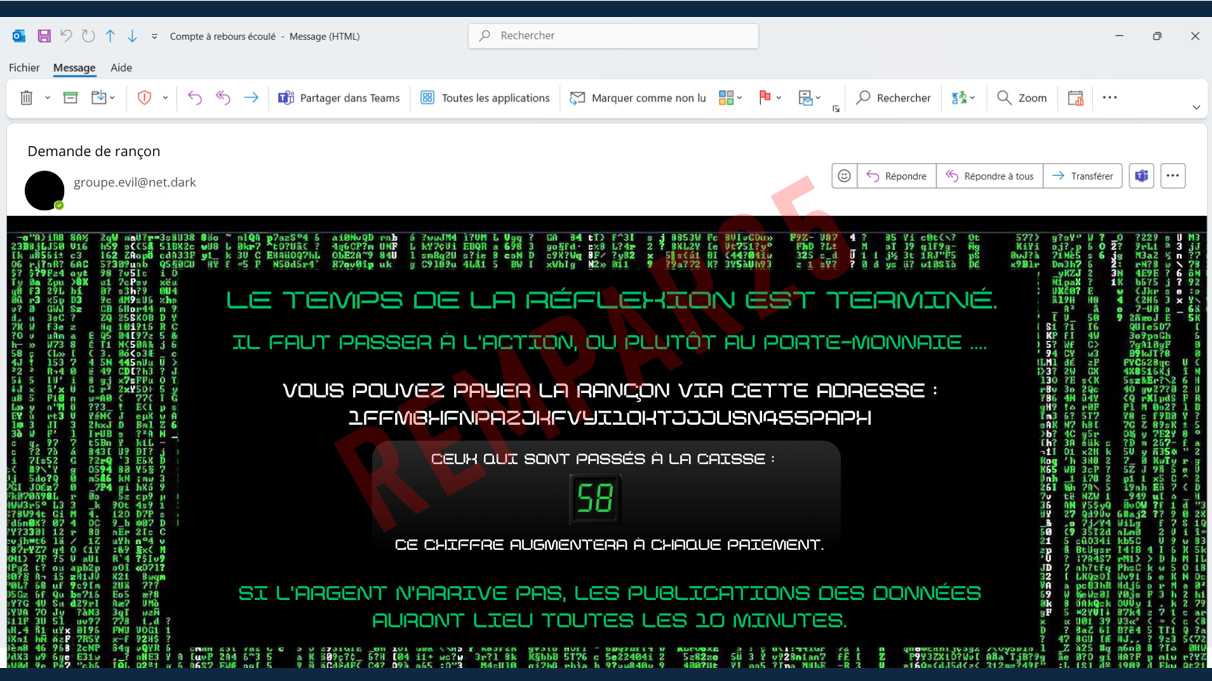

Screenshot of an email demanding a ransom.

Below is a detailed description of its content:

Email background:

- The message background is full of green characters against a black backdrop, resembling attacker’s interface as often seen in the movies. This style is no doubt used to reinforce the intimidating effect of the message.

- A “Ransomware” logo is superimposed diagonally on the image, emphasising the malevolent nature of the message.

- Content of the message:

- Ransom demand

- From: groupe.evil@net.dark

- The time for thinking is over. It’s time for action, which means it’s time to pay up…

You can pay the ransom via this address: (address composed of a series of numbers and letters).

Others who have already paid: 58

This figure will increase with each payment.

If the money doesn’t arrive, data will be published every ten minutes.

Example of a stimulus, sent by the IT department (the previous stimuli messages stated that there was a countdown on the screen): “The attacker group that contacted us has just announced that the countdown has now expired. They are threatening to publish a dataset extracted during the attack every ten minutes unless a ransom is paid. In place of the countdown, the following text now appears: “Others who have already paid, followed by a figure”. We believe that this figure will increment with each ransom payment made. Attached you will find screenshots of the elements shared.”

Another example, sent by a disgruntled employee: “Do you realise that no one is able to work properly this morning? I have to conduct a recruitment interview at 10:30. How am I going to do that under these conditions?” This is a good example of the messages that would arrive during a real attack, and would put the crisis unit under pressure.

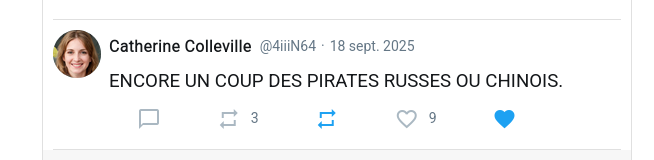

Speaking of pressure, ANSSI did an excellent job producing simulated media pressure, with a fake news website, a fake TV channel sensationalising the story, and even a fake social network4. This fake social network was perfectly functional and players could reply to messages. There was a mixture of “real” messages from players and “fake” messages sent by ANSSI, very similar to those found on a real social network (i.e. not necessarily the most useful).

Screenshot of a message posted on a social network.

Original message in French:

Message de Catherine Colleville, 18 sept. 2025

ENCORE UN COUP DES PIRATES RUSSES OU CHINOIS.

Here is the translation in English:

Message from Catherine Colleville, 18 Sept. 2025

RUSSIAN OR CHINESE PIRATES STRIKE AGAIN.

In each organisation, there were three categories of people. First there were the organisers, who prepared the event, wrote or amended the stimuli, decided on the local adaptations5, etc. During the event these organisers also played the role of people who would have been called upon in a real crisis, despite not being active participants.

The second category was that of the players, the people chosen to play themselves. They were u

The third category consisted of observers, who, as the name implies, simply observe, not saying anything but taking notes then used for “hot” and “cold” analyses, immediately upon conclusion of the event and in the following weeks, respectively.

Typically, players and observers are grouped together in a large hall, to facilitate communication and observation6. The organisers gather in a separate room, performing their role of non-players via telephone and email.

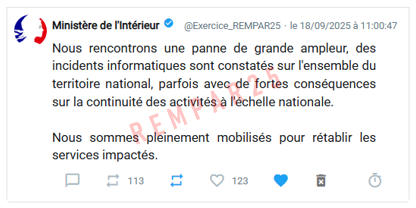

Screenshot of a message posted on a social network.

Original message in French:

Ministère de l’Intérieur @Exercice_REMPAR25 – le 18/09/2025 à 11:00:47

Nous rencontrons une panne de grande ampleur, des incidents informatiques sont constatés sur l’ensemble du territoire national, parfois avec de fortes conséquences sur la continuité des activités à l’échelle nationale.

Nous sommes pleinement mobilisés pour rétablir les services impactés.

Here is the translation in English:

Ministry of the Interior @Exercice_REMPAR25 – 18/09/2025 at 11:00:47

We are currently experiencing a widespread outage, with IT incidents occurring nationwide, sometimes with serious consequences for business continuity nationally.

We are using all our resources to try to re-establish the affected services.

The results

At the end of the day’s drill the results are analysed and an assessment it drawn up.

At present, REMPAR25 is in this phase of analysing the results and establishing conclusions and actions to be taken. Were any important stimuli ignored? Or did participants over-react to less important stimuli? All the participating organisations are busy combing through the results of the exercise and ANSSI will no doubt produce a review of the operation. Note, however, that many of the texts written for the drill will not be made public.

1 ANSSI did not say which software application, but some organisations adapted the exercise by choosing an application they themselves used in real life.

2 These consequences were less serious in France, however, where the software was much less common.

3 Remember that “security” software is not always necessarily installed in the interests of security but instead – in many cases – to meet regulatory or insurance compliance requirements.