Created in 1998 by the Clinton Administration to ensure the “privatisation” of Internet governance which had been overseen by American universities and research centres up until then, the acronym ICANN is well-known to those working in domain names.

And yet, its philosophy, its specific missions and its organisation remain largely unknown. This series of publications will lift the veil of mystery and perhaps help our readers better interact with ICANN.

There are three Supporting Organizations, which each elect two members of the ICANN Board, i.e. 6 out of 20. They provide input and represent the interests of three separate groups:

- IP address managers or Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) through the ASO (Address Supporting Organization)

- Generic TLD managers under the GNSO (Generic Names Supporting Organization)

- ccTLD registries, within the ccNSO (Country Code Names Supporting Organization)

We take a detailed look at the missions and structure of each of these Supporting Organizations. This time, the GNSO.

The GNSO and its missions

The GNSO (Generic Names Supporting Organization) is the structure whose activities receive the most media coverage, because it is through this Supporting Organization that ICANN plays its role as the coordinator of issues relating to management of TLDs (Top-Level Domains).

According to its bylaws, the GNSO “fashions, (and over time, recommends changes to) policies for generic Top-Level Domains. The GNSO strives to keep gTLDs operating in a fair, orderly fashion across one global Internet, while promoting innovation and competition.”

These few lines incorporate high stakes, because gTLDs include well-known domain names such as .com, .net and .org, but also all of the “new TLDs” created since 2013, i.e., around 65% of the domain names currently existing across the world.

The GNSO therefore focuses on organising the market through contractual relationships with its stakeholders, but also on defining the processes and rules governing their activities:

- process of creating new gTLDs and terms of contractual agreements between delegatees (or registries) and ICANN

- process of deleting gTLDs

- process of registrar accreditation and terms of contractual agreements between these registrars and ICANN

- definition of the minimum services required of registrars

- definition of the processes determining the life-cycle stages of domain names

- definition of the administrative procedures for dispute resolution

- management and access to WHOIS data

- etc.

The GNSO and its organisation

The GNSO has a particularly complex organisation on account of the large number of areas of expertise and interests at stake. We will set out its various components here, before taking a closer look at each later.

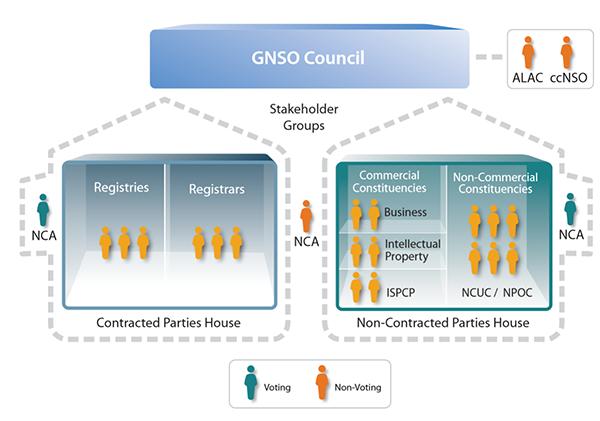

The GNSO Council is made up of 21 members divided into two “houses”, “like the US Congress or the British Parliament”.

https://gnso.icann.org/sites/default/files/gnso/images/gnso-structure-600×421-12oct14-en.png

The first “house”, the Contracted Parties House (CPH) holds the Registries and Registrars, i.e., the structures (mainly commercial) in a contractual agreement with ICANN. These are the economic players in the domain name sector whose activities are directly impacted by ICANN’s decisions.

The second “house”, the Non-Contracted Parties House (NCPH) holds stakeholders in the domain name market ecosystem that are not in a contractual agreement with ICANN. These bodies include different interest groups:

- the Constituencies including the following commercial players: Business Constituency, Intellectual Property Constituency, Internet Service and Connectivity Providers Constituency (ISPCP)

- the Constituencies including the following non-commercial players: Non-Commercial Users Constituency (NCUC) and Not-for-Profit Operational Concerns Constituency (NPOC)

ICANN’s Nominating Committee appoints three GNSO Council members, two of whom are voting members assigned to each House. The third appointee acts as an “advisor” to the Council as a whole. This advisor has no voting rights but can take part in discussions, etc.

The seats are therefore distributed as follows:

| Bodies | No. of

seats |

% of votes

|

|

| Contracted Parties House | Registries Stakeholder Group | 3 | 15% |

| Registrars Stakeholder Group | 3 | 15% | |

| Appointed by the Nominating Committee | 1 | 5% | |

| Total CPH | 7 | 35% | |

| Non-Contracted Parties House | Commercial Stakeholder Group | 6 | 30% |

| of which the Commercial Business Users Constituency | 2 | 10% | |

| of which the Intellectual Property Interests Constituency | 2 | 10% | |

| of which the Internet Service and Connection Providers | 2 | 10% | |

| Non-Commercial Stakeholder Group | 6 | 30% | |

| of which Non-Commercial Users Constituency (NCUC) | 3 | 15% | |

| of which Not-for-Profit Operational Concerns Constituency (NPOC) | 3 | 15% | |

| Appointed by the Nominating Committee | 1 | 5% | |

| Total NCPH | 13 | 65% | |

| Council Advisor (non-voting) | Appointed by the Nominating Committee | 1 | – |

| Total GNSO Council | – | 21 |

The Council also includes non-voting Liaisons and Observers from other groups within ICANN: ccNSO (Country Code Names Supporting Organization), GAC (Governmental Advisory Committee) and ALAC (At-Large Advisory Committee).

According to ICANN, this “elaborate system provides checks and balances so no single interest group can dominate the Council”. However, it is not easy to assess this principle of balance powers. For instance, members appointed by the Nominating Committee, though they only have 10% of nominal voting rights, can exercise significant influence over decisions as they both hold votes that are likely to sway voting results in situations where the two stakeholders making up the CPH and the NCPH find themselves opposing each other. Registries and registrars can indeed have divergent, if not antagonistic, interests in certain subjects; the same goes for holders of commercial and non-commercial interests.

One particular factor is that some players with a direct economic interest in influencing ICANN’s decisions one way or another are able to finance “permanent” representatives within the working groups, while others, acting intuitu personae on a voluntary basis, are unable to get involved to such an extent. In other cases, players with a “vital” interest in seeing a decision through will fight fiercely for it, while more indifferent players will only obstruct it in extreme cases. The decision-making principle being that of consensus, those who know what they want and who are highly involved will generally get the better of those who do not have a strong stance and/or who cannot take part in all the discussions.

It should be noted that this organisation dates back to before the activity of back-end registry operator existed as such. Today, these players can be all the more influential as they divide their time between managing generic TLDs and geographic TLDs.