The SPF, DKIM and DMARC authentication protocols form a bulwark against a structural problem of email: the ease of e-mail address spoofing. One year on from our initial study on the adoption of SPF, DKIM and DMARC in the .fr zone, here is an update.

Afnic’s study published last year was based on a snapshot of the .fr TLD taken between 30 and 31 January 2023. This snapshot combined data obtained via the DNS and the presence of a website associated with the domain name with original content. A similar methodology was used for this year’s snapshot and the data were collected around 15 February 2024.

We collected data on over 4 million .fr domain names, 3.9 million of which were working.

These data gave us direct access to the SPF and DMARC policies and enabled us to infer the presence of at least one DKIM key. This year we also included BIMI (Brand Indicators for Message Identification) in the study and we looked for BIMI assertion records using the default selector.

In this note, we will review the most notable changes between 2023 and 2024 before returning to the details of the study. We will also try to explain the changes we see, before ending with the possible future prospects.

SPF, DKIM, DMARC: What’s it all about?

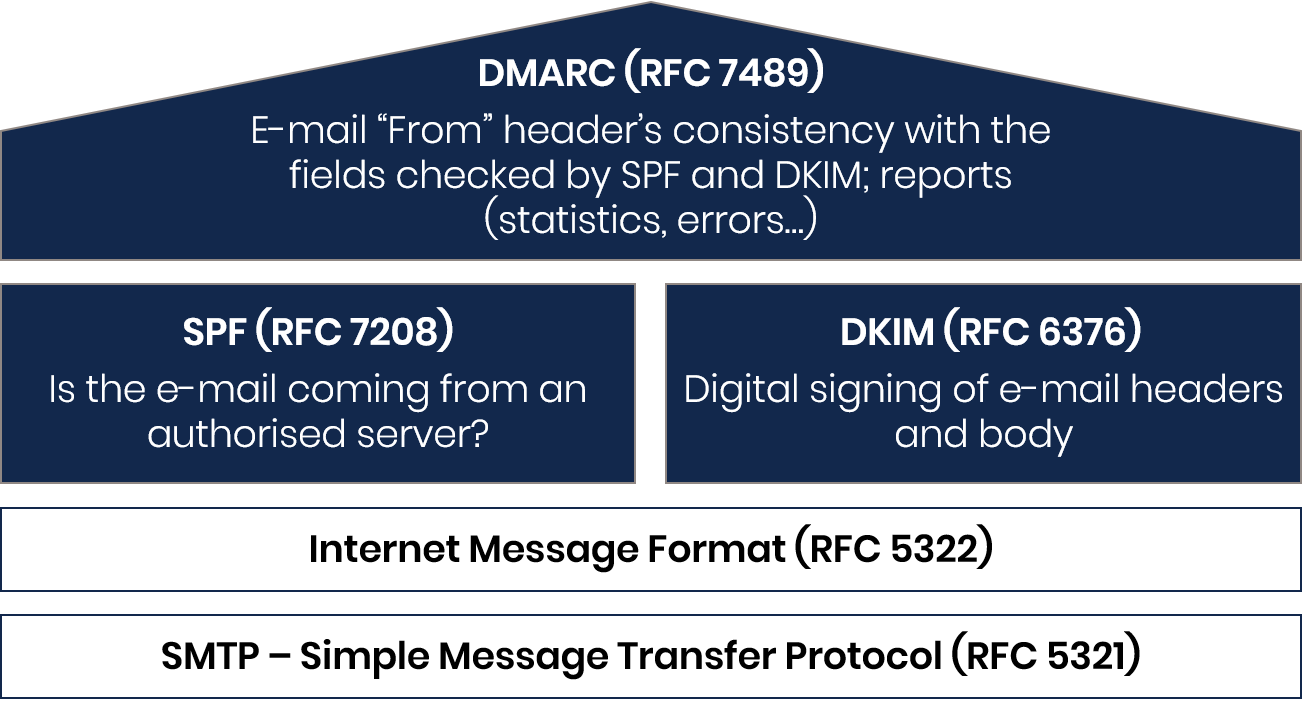

For those who have not yet read the previous blog entries on this subject, here is a reminder of what SPF, DKIM and DMARC are and what they are used for:

- Sender Policy Framework (SPF) is a mechanism whereby the administrator of a domain name can designate, by means of information published in the DNS, the list of mail servers authorised to send messages purporting to come from that domain name;

- Domain Keys Identified Mail (DKIM) is a mechanism allowing a messaging server to confirm that an email does actually come from a given domain name by means of digital signatures affixed to the messages, the public keys for which are published in the DNS;

- lastly, Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Compliance (DMARC) performs additional consistency checks relying on SPF and DKIM to determine the authenticity of messages. The administrator of a domain publishes a DMARC policy in the DNS that plays two main roles: firstly, it recommends an action if the email fails the checks (do nothing, quarantine or reject the message); secondly, it provides an email address for receiving automated reports, allowing the deliverability of the messages to be monitored.

These three mechanisms together constitute a counter-measure that should make email identity theft much more difficult.

On top of SPF, DKIM and DMARC comes Brand Indicators for Message Identification (BIMI), a mechanism for displaying logos on emails that pass the DMARC test.

A diagram in the shape of a house with four storeys.

The ground floor is a block indicating “SMTP – Simple Message Transfer Protocol (RFC 5321)”.

On the first floor, there is a block indicating “Internet Message Format (RFC 5322)”.

On the second floor, there are two blocks, side by side. The one on the left says: “SPF (RFC 7208): Is the e-mail coming from an authorised server?” The one on the right says: “DKIM (RFC 6376): Digital signing of e-mail headers and body.”

On the top floor, a block forming the roof carries the text: “DMARC (RFC 7489): E-mail ‘From’ header’s consistency with the fields checked by SPF and DKIM; reports (statistics, errors…)”.

The two upper floors are in a different colour from the two lower ones, suggesting that the construction above RFC 5321 and 5322 is much more recent than the original building.

Notable changes

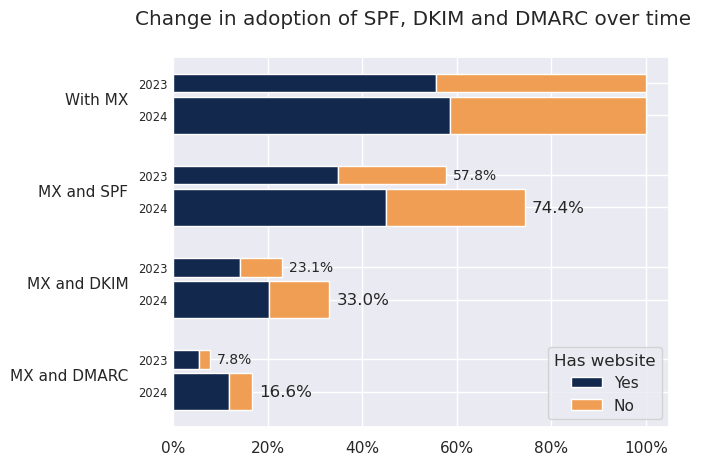

The first thing to note is the clear increase in the adoption of SPF, DKIM and DMARC in the .fr TLD. Indeed, among .fr domains that publish at least one MX record:

- 74.4% of them publish an SPF policy (compared to 57.8% in 2023);

- 33.0% of them seem to have deployed DKIM (compared to 23.1% in 2023);

- and 16.6% publish a DMARC policy (compared to 7.8% in 2023).

Between 2023 and 2024, the proportion of domain names with an original website remained practically unchanged: just over half the domains with at least one MX record have their own website.

Among the domains with at least one MX record:

- the proportion having an SPF policy went from 57.8% in 2023 to 74.4% in 2024.

- the proportion for which we inferred the deployment of DKIM went from 23.1% in 2023 to 33.0% in 2024.

- lastly, the proportion having a DMARC policy went from 7.8% to 16.6%.

Looking at all domains, including those that do not publish an MX record at the apex, we find that 66.2% publish an SPF policy, 28.5% seem to have deployed DKIM and 15.1% publish a DMARC policy. These figures were respectively 52.5%, 22.6% and 7.3% in 2023.

Regarding SPF, adoption did not increase at the cost of quality: best practices are better adhered to on average, and the proportion of SPF policies adhering to all of them increased from 97.74% to 98.82%.

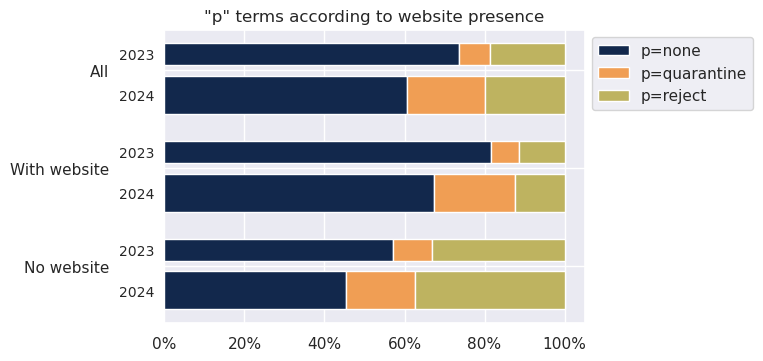

For DMARC, findings are similar: in particular we see a reduction in the use of the p=none policy, mainly in favour of p=quarantine policies, while the advance of the p=reject policy was limited almost entirely to domains with no website.

BIMI also made an appearance, but only very tentatively. It was adopted by just 2,295 domains with at least one MX Entry. And of these few, the vast majority have deployed BIMI incompletely: only 58 .fr domains publish a BIMI assertion record with the VMC (Verified Mark Certificate) required by some messaging providers as a requirement for displaying a logo.

Detailed results of the study

Let us look now at some details that emerge from this year’s study: the improvement in how SPF best practices are adhered to, the way DMARC policies have evolved and an analysis of BIMI in the .fr TLD.

SPF best practices

Last year we listed the following principles as best practices for preparing and publishing an SPF policy:

- publish a policy with correct syntax;

- publish one and only one SPF policy;

- publish the SPF policy as a DNS TXT type record; do not use the DNS “SPF” type;

- be sufficiently restrictive, which means don’t authorise everything by default (

+allorallterms must not be used) and don’t allow more than 216 IPv4 addresses or 232 /64 IPv6 subnets; - don’t use the

ptrmechanism or the%{p}macro; - don’t list IP addresses in ranges that are either non-routable or meant for private addressing;

- keep the size of a TXT record set below 512 bytes;

- publish a policy requiring at most ten DNS requests to evaluate.

Comparing adherence to best practices between 2023 and 2024, we see a clear improvement in the quality of SPF policies to judge from the following indicators.

Table 1:

Comparison of adherence to best practices in SPF policies in the .fr zone between 2023 and 2024

|

2023 |

2024 |

|

|

Being sufficiently restrictive |

97.74% |

99.75% |

|

Non-use of the DNS SPF type |

98.69% |

98.82% |

|

Absence of |

98.94% |

99.48% |

|

Uniqueness of the SPF policy |

99.16% |

99.41% |

|

Absence of non-routable IPs |

99.61% |

99.68% |

|

TXT record set ⩽ 512 bytes |

99.74% |

99.71% |

|

Absence of syntax errors |

99.83% |

99.83% |

|

SPF policy ⩽ 10 DNS requests |

99.995% |

99.996% |

All these metrics have increased, except one. The exception is the proportion of domains where the set of TXT records at the apex did not exceed 512 bytes, which fell slightly.

Size of the sets of TXT records

Why are we so interested in looking at this indicator in particular?

Originally, DNS messages exchanged by UDP could not exceed 512 bytes. Responses exceeding this limit have to be truncated and indicated as such by the authoritative name server; the resolver then has to repeat the same request using TCP to obtain a complete set of records, which is much more costly.

And although the EDNS extension mechanism allows the maximum size of messages over UDP to be increased, an examination of DNS traffic on Afnic’s authoritative name servers between February and April 2024 shows that 19.5% of the traffic comes from resolvers that have not implemented EDNS. So staying under 512 bytes still makes sense.

SPF policies are published in the form of TXT records at the apex of the domain (i.e. directly on domain.example, rather than on a subdomain as in the case of DMARC). They coexist with other TXT records that some cloud software platform publishers require to prove one’s control over a domain.

A customer of many suppliers of software of this type, who all require this verification method will therefore find that his set of TXT records grows and eventually becomes too large to be served using UDP, which may degrade performance every time a mail server wishes to obtain the SPF policy of the domain concerned.

Suppliers who impose TXT at the apex participate in what is now considered as a bad practice by an Internet Draft. This document recommends among other things placing this type of TXT in subdomains.

DMARC policies

In broad terms, let us first recall that DMARC allows the domain holder to recommend an action when an incoming email simultaneously fails both the SPF and the DKIM checks. There are three possibilities: p=reject in a DMARC policy means “reject: do not let this message through”; p=none conversely, means “no action: let this message through” and between these two extremes is p=quarantine, which suggests quarantining the message, for example by storing it in an appropriate sub-folder or in a queue pending more detailed examination. In this latter case, the message is quarantined with a probability expressed as a percentage by the term pct, which by default is 100.

The sharp rise in the adoption of DMARC goes hand in hand with a clear reduction in the proportion of p=none policies, mainly in favour of p=quarantine. As for the p=reject policy, it showed only a very small increase among domains publishing a website but a more significant one among those with no website.

Among all the domain names publishing a DMARC policy, we compare the proportions of the terms “p=none”, “p=quarantine” and “p=reject”.

Between 2023 and 2024, use of the “p=none” policy fell from 73.5% to 60.6%, while “p=quarantine” increased from 7.9% to 19.4% and “p=reject” from 18.5% to 20.0%.

The figure also makes the same comparison limited to domain names with a DMARC policy and a website with original content.

Among these, between 2023 and 2024, use of the “p=none” policy fell from 81.6% to 67.4%, while that of “p=quarantine” rose from 7.0% to 20.3% and “p=reject” went from 11.3% to 12.3%.

Lastly, among the domain names with a DMARC policy but no website with original content, use of the “p=none” policy fell from 57.2% to 45.4%, while that of “p=quarantine” rose from 9.8% to 17.2% and “p=reject” from 33.0% to 37.3%.

So DMARC policies are both more numerous and stricter: in theory .fr domain names are better protected against email identity theft. But the number of domains is still tiny: just 117,243 domains published a p=reject, i.e. 2.99% of the total number of .fr domain names; the proportion was 1.34% last year.

This suggests that some domain holders decided to transition from the p=none to the p=quarantine policy. The transition to p=reject is therefore still seen as risky: the proportion of domains with online presence using the p=reject policy has hardly increased at all.

As for domains without a website, we also see use of the p=none policy in free fall. This fall is partly in favour of p=quarantine, but we also see more domains opting for p=reject. At this rate, next year p=reject may surpass p=none among these domains.

And BIMI?

Let us now look more closely at the adoption of BIMI by .fr domains.

First of all, what is BIMI? BIMI, or Brand Indicators for Message Identification, is an emerging draft specification for displaying brand logos next to emails from a given business that have been authenticated by means of SPF, DKIM and DMARC. The logo is displayed only if the domain publishes a sufficiently strict DMARC policy.

The domain holder publishes a TXT record known as a “BIMI assertion record” in the DNS. It contains two pieces of information: the URL of the image of the logo to be displayed and the URL of a certificate evidencing the right to use the image, known as the VMC or Verified Mark Certificate. An example:

default._bimi.domaine.example IN TXT ( "v=BIMI1; l=https://domaine.example/logo.svg; " "a=https://domaine.example/vmc.pem" )

The road to the adoption of BIMI is a long one

The complete deployment of BIMI requires many prior steps.

First of all, it is necessary to have put a p=reject, or p=quarantine DMARC policy in place and for the pct term to be either not specified or 100. This in turn implies having first put in place SPF and DKIM.

Next the logo has to be made available in SVG format (more precisely, a specific SVG profile), and then the BIMI assertion record consisting of just one term l= has to be published. This type of BIMI record is referred to as “self-asserted”, since it does not refer to a certificate.

However, some messaging services insist on “certified” records on the logical basis that it would be easy for a malicious actor to register a domain usurping a brand, configure SPF, DKIM and DMARC correctly and copy the logo in the BIMI assertion. To obtain a certified record it is necessary to follow all the same steps as for the self-asserted record, and to register the trademark and the logos with the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI), or equivalent, buy a VMC and add the URL of this certificate to the BIMI assertion record.

Very low rate of adoption

So where are we with the adoption of BIMI? The adoption rate is very low. What adoption there is, is seen mainly with domains having a website with original content, as shown in the table below.

Table 2:

Adoption of BIMI in the .fr zone

|

Website |

Domain names |

With MX and BIMI |

Proportion |

|

Yes |

2,238,330 |

1,582 |

0.071% |

|

No |

1,677,088 |

713 |

0.043% |

|

Total |

3,915,418 |

2,295 |

0.059% |

Looking more closely at these domains, we find:

- 968 unique, non-null BIMI assertion records;

- including: 70 records showing the URL of a VMC (the remainder are self-asserted);

- and of these 70 VMC URLs:

- 58 point to X.509 certificates conforming to the requirements for this type of certificate,

- three point to X.509 certificates that do not conform (for example, TLS certificates, which are also in X.509 format),

- four give a 404 error when attempting to access them,

- and 5 redirect to something other than an X.509 certificate (images, GPG keys, etc.)

Lastly we note that among these 58 VMCs, the market is dominated by two certificate authorities: DigiCert (42 certificates) and Entrust (16 certificates), both based in the United States.

Examination of VMCs

Each business obtaining a VMC was classified manually in a business sector. The results show that they are practically all large groups and that no public service has adopted BIMI. The sectors most represented are:

- e-commerce (15 VMCs);

- financial services (14 VMCs);

- and new information and communication technologies (NICTs, 8 VMCs).

The table below shows the distribution of businesses that have adopted a VMC by sector, in greater detail.

Table 3:

Business sectors of undertakings that have invested in a VMC, among the certificates found in BIMI records in the .fr zone

|

Category |

Sub-category |

Number |

|

E-commerce |

General |

5 |

|

E-commerce |

Fashion |

5 |

|

E-commerce |

Specialised (other than fashion) |

5 |

|

Financial services |

Banks |

8 |

|

Financial services |

Insurers |

4 |

|

Financial services |

Others |

2 |

|

Miscellaneous |

Others |

6 |

|

Miscellaneous |

Education |

2 |

|

Miscellaneous |

Food |

2 |

|

Miscellaneous |

Health |

2 |

|

Miscellaneous |

Media |

2 |

|

Miscellaneous |

Travel |

2 |

|

NICTs |

All |

8 |

Explanation of changes

There are four trends that in my opinion underpin the changes described above: e-mail service providers starting to require SPF, DKIM and DMARC; the attractiveness of BIMI; the influence of other industries and public services and the new modi operandi of certain types of fraudsters.

E-mail service providers

E-mail service providers, which are anxious to protect their users from fraudulent emails, are starting to be more demanding as regards the messages they will accept, particularly those coming from domains that see heavy traffic.

For example, since 1 February of this year, Gmail requires sender domains to have SPF or DKIM (at least one of the two). And bulk senders (more than 5,000 emails a year) to have SPF, DKIM and DMARC. Yahoo has had the same requirements since the same date.

Gmail and Yahoo! together reportedly have more than 1.7 billion users. 1.7 billion mailboxes that have become inaccessible to domains that do not deploy SPF, DKIM or DMARC.

This trend looks set to continue: if Gmail and Yahoo Mail start to demand SPF, DKIM and DMARC, other e-mail service providers, anxious to protect their users from fraudulent messages, might be more likely to follow them, since the emailing industry has already adapted.

BIMI and its appeal

A second explanation is BIMI. In order for a e-mail service provider implementing BIMI to display the logo associated with the sender domain, one of the prerequisites is the publication of a strict DMARC policy, in other words p=quarantine without the term pct or with the term pct=100, or p=reject.

But it is still too soon to be able to say whether it is these strict prerequisites that are slowing the rate of adoption of BIMI or if, on the contrary, it is the prospect of displaying logos to customers that is encouraging people to put SPF, DKIM and DMARC in place with a view to subsequently deploying BIMI.

Other industries and governments

Other industries are also pushing for the adoption of SPF, DKIM and DMARC. This is particularly the case of PCI DSS (Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard), a set of rules aimed at protecting financial data. Version 4.0 of the PCI DSS standard will make it obligatory for SPF, DKIM and DMARC to be put in place with effect from 1 April 2025.

We note also the initiative of the German Federal Government, whose Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik (Federal Agency for Information Technology Security or BSI) published a set of technical requirements in February 2024 (in English and German) on the authentication of emails, entirely devoted to SPF, DKIM and DMARC.

Other considerations

Lastly, at a time when generative AI is raising concerns as to its potential for enabling phishing campaigns that are convincing, or worse yet, highly customised (spear phishing), being able to trust message headers has become all the more important. What’s more, it has now been proven that state actors, such as North Korea, do not hesitate to abuse poorly protected domains to carry out targeted phishing campaigns.

Future stakes

All these observations lead us to wonder about two subjects in particular: the effectiveness of SPF, DKIM and DMARC when the sending of emails is outsourced to third party undertakings and the possible domination of the market for VMCs for BIMI by actors based in the United States.

Outsourcing of emails: source of failings for SPF, DKIM and DMARC?

The effectiveness of SPF is based on the assumption that each domain has its own infrastructure for sending emails, with no sharing of resources. Entrusting the sending of messages to a third party, whether this is a hoster, an application platform or a “router”, goes against this assumption and therefore weakens the safeguards provided by SPF.

In particular, outsourcing the sending of emails in this way requires the inclusion in one’s own SPF policy of a subpolicy controlled by the provider listing large ranges of IP addresses. Yet there is nothing to prevent a provider’s customer from spoofing the identity of another customer of the same provider if they both have to publish lax SPF policies. SPF is not an effective counter-measure in this scenario. With the slightest use of the include option, the quality of the domain’s SPF policy becomes directly dependant on that of the sub-policies.

This weakening of SPF’s safeguards also entails a weakening of DMARC’s, which in turn creates the risk of accidentally displaying a business’s logo next to a fraudulent email.

BIMI and certificate authorities: are we heading for market concentration around U.S. actors?

The development of BIMI entails the emergence of a new market of issuers of VMCs, parallel to that of issuers of TLS certificates. All VMCs seen during the study were issued by entities based in the United States.

There are some French bodies from which certificates appropriate for BIMI can be obtained, but they are resellers of the U.S. companies DigiCert and Entrust. That said, there is no trace of the reseller in the certificate.

In order for a French certificate authority to emerge in this market, it would first need to convince e-mail service providers to trust the certificates it issues. This problem is analogous to that of the TLS certificates, where any new certificate authority needs to find a way into the certificate authority bundle that Web browsers trust by default.

Conclusion

In this note we have seen how the adoption of SPF, DKIM and DMARC has changed for the better. This is a virtuous circle: the more these mechanisms are adopted, the more indispensable they become. But if poorly configured, they can come back to haunt the domain name holders concerned. For this reason it is important to know how to configure SPF, DKIM and DMARC correctly.

To this end, Afnic offers a training course on SPF, DKIM and DMARC intended for IT professionals and domain holders. While waiting for the next session, you can also explore the other resources that Afnic makes available on the same subject:

- the Zonemaster tool, which includes a test of the syntax of SPF policies;

- a presentation and an on-stage demonstration of SPF, DKIM and DMARC in the Afnic Scientific Council Open Day (JCSA) in 2023, which you can watch on video (in French);

- and the source code of the SPF, DKIM and DMARC tutorial used in this on-stage demonstration.

And what about you? Is your domain name protected against malicious actors?